The Experiences of Women in WWI

When we commemorate those who lost their lives in the First World War and other conflicts over the course of the 20th century on 11th November at 11.00am (the time when this conflict came to an end), this has come to be a moment when we reflect upon the nine million soldiers and seven million civilians who died in the “Great War” of 1914 to 1918. When stories of heroism are mentioned, most focus on the brave men who fought in the trenches.

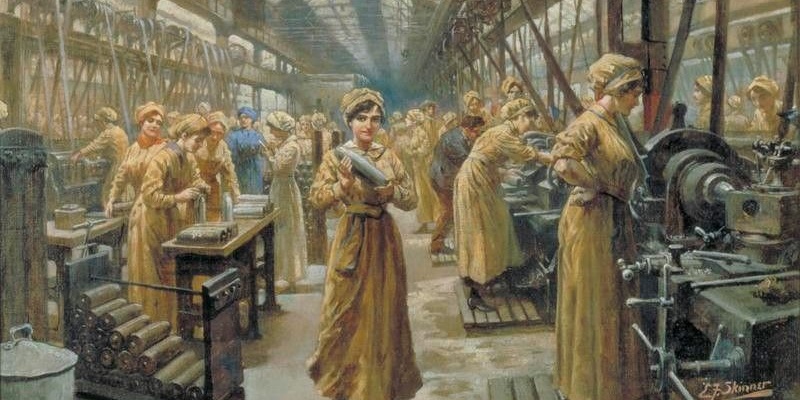

Women were not allowed in military service at this time and their contributions and experiences in the conflict, whether in terms of working in munitions factories, helping wounded soldiers or taking an active part in other aspects of war work, has often been neglected.

Women were not allowed in military service at this time and their contributions and experiences in the conflict, whether in terms of working in munitions factories, helping wounded soldiers or taking an active part in other aspects of war work, has often been neglected.

The Experiences of Vera Brittain

Born in 1893, Vera Brittain in Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire would have a distinguished career as a writer and feminist during the 20th century, with her ideas and beliefs being very much shaped by the experiences she had as a young woman during World War I which she wrote about in “Testament of Youth”.

Born in 1893, Vera Brittain in Newcastle-under-Lyme in Staffordshire would have a distinguished career as a writer and feminist during the 20th century, with her ideas and beliefs being very much shaped by the experiences she had as a young woman during World War I which she wrote about in “Testament of Youth”.

Early Life and Background

Vera Brittain came from a comfortable background, growing up with younger brother Edward in Macclesfield and Buxton before attending boarding school in Surrey from the age of 13, where she did very well & wanted to continue with her studies at university, although this was opposed by her parents for two years. In 1914, Vera was finally allowed to go to university, becoming an undergraduate at Somerville College, Oxford, where she read English Literature, although to Vera this came to be seen as not being a priority over the course of 1914 to 1915 with the outbreak of World War I and the enlistment of her male contemporaries.

Vera Brittain and the Voluntary Aid Detachment

In 1915, Vera took the decision to delay her studies to work as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse, which was disapproved of by her parents in the same way as her desire to go to university had been and, over the course of the next three years, she served in hospitals in Buxton, London, Malta, and France. Part of the reason for Vera deciding to leave Oxford and join the VAD was the fact that her younger brother Edward had enlisted in the armed forces along with his friends from school, Roland Leighton (to whom Vera became engaged), Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, all of whom she developed close emotional ties.

In 1915, Vera took the decision to delay her studies to work as a Voluntary Aid Detachment nurse, which was disapproved of by her parents in the same way as her desire to go to university had been and, over the course of the next three years, she served in hospitals in Buxton, London, Malta, and France. Part of the reason for Vera deciding to leave Oxford and join the VAD was the fact that her younger brother Edward had enlisted in the armed forces along with his friends from school, Roland Leighton (to whom Vera became engaged), Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, all of whom she developed close emotional ties.

Tragedy and Loss in World War I

Tragically, in December 1915, Roland Leighton was killed by snipers on the Western Front while attempting to repair barbed wire on the front line in France and, as a strategy of dealing with her grief, Vera concentrated on her work as a nurse and helping wounded soldiers, especially as her brother Edward was going to France. Over the course of 1916, Vera kept in touch with her brother Edward, who was injured at the Battle of the Somme, and Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, who were also injured out of the conflict, before Thurlow died in military action in April 1917 and Richardson as a result of his injuries in June of the same year.

Tragically, in December 1915, Roland Leighton was killed by snipers on the Western Front while attempting to repair barbed wire on the front line in France and, as a strategy of dealing with her grief, Vera concentrated on her work as a nurse and helping wounded soldiers, especially as her brother Edward was going to France. Over the course of 1916, Vera kept in touch with her brother Edward, who was injured at the Battle of the Somme, and Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow, who were also injured out of the conflict, before Thurlow died in military action in April 1917 and Richardson as a result of his injuries in June of the same year.

The Death of Edward Brittain

During all of this time, Vera continued to serve with the VAD, being stationed in France and Malta, keeping in touch with brother Edward on a regular basis through letters, particularly as he was moved from the Western Front in France after the battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), to the Italian Front. In June 1918, Edward Brittain led his men on a counterattack against enemy Austrian forces on the front line after suffering heavy bombardment, but was shot through the head by a sniper & died instantaneously after having survived so many other attacks in the war.

During all of this time, Vera continued to serve with the VAD, being stationed in France and Malta, keeping in touch with brother Edward on a regular basis through letters, particularly as he was moved from the Western Front in France after the battle of Ypres (Passchendaele), to the Italian Front. In June 1918, Edward Brittain led his men on a counterattack against enemy Austrian forces on the front line after suffering heavy bombardment, but was shot through the head by a sniper & died instantaneously after having survived so many other attacks in the war.

Vera Brittain and the Writing of “Testament of Youth”

As a result of her experiences as a nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment & the deaths of her brother, fiancé and two close associates (Edward, Roland, Victor, and Geoffrey), Vera became a committed pacifist following the end of the war in 1918, writing up her experiences of this time in “Testament of Youth”. After the war, Vera returned to Oxford to complete her studies and, although she switched from English Literature to History, she went on to become an acclaimed writer, although the poem “Perhaps” which she wrote following the death of Roland Leighton in 1915 & dedicated to him remains a powerful epitaph to all loss in war.

As a result of her experiences as a nurse in the Voluntary Aid Detachment & the deaths of her brother, fiancé and two close associates (Edward, Roland, Victor, and Geoffrey), Vera became a committed pacifist following the end of the war in 1918, writing up her experiences of this time in “Testament of Youth”. After the war, Vera returned to Oxford to complete her studies and, although she switched from English Literature to History, she went on to become an acclaimed writer, although the poem “Perhaps” which she wrote following the death of Roland Leighton in 1915 & dedicated to him remains a powerful epitaph to all loss in war.

Vera Brittain and “Perhaps”

Although Brittain did get married and have children during the 1920s, it is widely believed that the tragedies of the deaths of Roland Leighton, Edward Brittain, Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow remained with her all her life until her death in 1970, especially the death of Roland Leighton as indicated in “Perhaps”.

Although Brittain did get married and have children during the 1920s, it is widely believed that the tragedies of the deaths of Roland Leighton, Edward Brittain, Victor Richardson and Geoffrey Thurlow remained with her all her life until her death in 1970, especially the death of Roland Leighton as indicated in “Perhaps”.

“Perhaps some day the sun will shine again,

And I shall see that still the skies are blue.

And feel once more I do not live in vain,

Although bereft of You.

Perhaps the golden meadows at my feet

Will make the sunny hours of Spring seem gay.

And I shall find the white May blossoms sweet,

Though You have passed away.

Perhaps the summer woods will shimmer bright,

And crimson roses once again be fair,

And autumn harvest fields a rich delight,

Although You are not there.

Perhaps some day I shall not shrink in pain

To see the passing of the dying year,

And listen to Christmas songs again,

Although You cannot hear.

But, though kind Time may many joys renew,

There is one greatest joy I shall not know

Again, because my heart for loss of You

Was broken, long ago.”

The Experiences of Elsie Inglis

Eliza “Elsie” Inglis was born in 1864 in India, which at the time formed part of the British Empire, where her father was a magistrate who worked for the Indian Civil Service and, over the course of her life, would qualify as a doctor and become a medical surgeon, both of which were highly unusual for women at this time.

Eliza “Elsie” Inglis was born in 1864 in India, which at the time formed part of the British Empire, where her father was a magistrate who worked for the Indian Civil Service and, over the course of her life, would qualify as a doctor and become a medical surgeon, both of which were highly unusual for women at this time.

Elsie Inglis and Challenging the Medical Establishment

On the retirement of her father from the Indian Civil Service, Elsie returned to Britain, settling in Scotland, which was the home of the family, and in 1887, following the completion of her formal education, she started her studies at the Edinburgh School of Medicine for Women opened by Dr Sophia Jex-Blake. After her graduation in 1892, Elsie gained a job at the New Hospital for Women in London, set up by Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, before returning to Edinburgh in 1894 to work in several medical institutions in the city during the period up to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

Elsie Inglis and Challenging the Military and Political Establishment

Although Elsie was over 50 by the time the conflict started, this would be the part of her life to which she would make the greatest contribution, setting up the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service Commission to provide medical support for the British Armed Forces fighting in Europe. In spite of considerable opposition and a lack of financial support from the British authorities, Inglis was able to send 14 all-female teams of doctors, nurses and technical support teams to Belgium, France, Serbia and Russia, which was very remarkable after originally being told “my good lady go home and sit still”.

Although Elsie was over 50 by the time the conflict started, this would be the part of her life to which she would make the greatest contribution, setting up the Scottish Women’s Hospitals for Foreign Service Commission to provide medical support for the British Armed Forces fighting in Europe. In spite of considerable opposition and a lack of financial support from the British authorities, Inglis was able to send 14 all-female teams of doctors, nurses and technical support teams to Belgium, France, Serbia and Russia, which was very remarkable after originally being told “my good lady go home and sit still”.

Elsie Inglis and her Contribution towards Medical Treatment in the War

Elsie herself went to support the war on the Serbian Front in Southeastern Europe, working to improve hygiene amongst the soldiers, resulting in outbreaks of typhus and other epidemics being reduced significantly, although she was captured by German and Austrian forces and repatriated to Britain in 1916. The experiences Elsie faced in Serbia did not deter her from entering conflict zones and, in the same year, headed for the Russian Front in Eastern Europe and set up a hospital at Braila in Romania in which just 7 doctors, including herself, came to be responsible for treating 11,000 wounded soldiers and sailors.

Elsie herself went to support the war on the Serbian Front in Southeastern Europe, working to improve hygiene amongst the soldiers, resulting in outbreaks of typhus and other epidemics being reduced significantly, although she was captured by German and Austrian forces and repatriated to Britain in 1916. The experiences Elsie faced in Serbia did not deter her from entering conflict zones and, in the same year, headed for the Russian Front in Eastern Europe and set up a hospital at Braila in Romania in which just 7 doctors, including herself, came to be responsible for treating 11,000 wounded soldiers and sailors.

The Death and Impact of Elsie Inglis

In 1917 Elsie was forced to return to Britain, having contracted bowel cancer and died shortly after arriving back in the country, although by this time her efforts in the war had been recognised by politicians in Britain and Serbia and in the latter she became the first woman to hold the Serbian Order of the White Eagle. After the death of Inglis in 1917 a memorial fountain was constructed in the town of Mladenovac in Serbia where her hospital had been set up during World War I and had helped save the lives of many Serbian soldiers fighting for the Allies against Germany and Austria in the conflict.

In 1917 Elsie was forced to return to Britain, having contracted bowel cancer and died shortly after arriving back in the country, although by this time her efforts in the war had been recognised by politicians in Britain and Serbia and in the latter she became the first woman to hold the Serbian Order of the White Eagle. After the death of Inglis in 1917 a memorial fountain was constructed in the town of Mladenovac in Serbia where her hospital had been set up during World War I and had helped save the lives of many Serbian soldiers fighting for the Allies against Germany and Austria in the conflict.

The Experiences of Flora Sandes

Flora Sandes was born in 1876 and, during her early life, enjoyed various outdoor pursuits such as riding and shooting and even learned to drive a car during the first decade of the 20th century, with all of these activities being against conventions at the time and what women were expected to do with their time.

Flora Sandes before the First World War

After she had completed her formal education at school, Flora trained with the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), which was founded in 1907 as an all-women mounted paramilitary organisation in which its members learned first aid as well as horsemanship, together with military aspects such as signalling and drill. In 1910, Flora left the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry and helped establish a new organisation called the Women’s Sick and Wounded Convoy Corps with its purpose being to assist soldiers in war zones, and in 1912 it saw service in Bulgaria and Serbia during the First Balkan War.

After she had completed her formal education at school, Flora trained with the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry (FANY), which was founded in 1907 as an all-women mounted paramilitary organisation in which its members learned first aid as well as horsemanship, together with military aspects such as signalling and drill. In 1910, Flora left the First Aid Nursing Yeomanry and helped establish a new organisation called the Women’s Sick and Wounded Convoy Corps with its purpose being to assist soldiers in war zones, and in 1912 it saw service in Bulgaria and Serbia during the First Balkan War.

Nursing and Ambulance Driving in Serbia

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Flora volunteered to become a nurse, but she was rejected because of a lack of qualifications and instead joined a St John Ambulance unit and left Britain for Serbia on 12th August with 36 women to try and assist the crisis which had developed in this part of the war. On arriving at Kragujevac in Serbia, which was a base for the Serbian army which was attempting to prevent the Austrian army from conquering the country, Flora joined the Serbian Red Cross and became a nurse and ambulance driver providing medical assistance to injured soldiers in the conflict.

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, Flora volunteered to become a nurse, but she was rejected because of a lack of qualifications and instead joined a St John Ambulance unit and left Britain for Serbia on 12th August with 36 women to try and assist the crisis which had developed in this part of the war. On arriving at Kragujevac in Serbia, which was a base for the Serbian army which was attempting to prevent the Austrian army from conquering the country, Flora joined the Serbian Red Cross and became a nurse and ambulance driver providing medical assistance to injured soldiers in the conflict.

Flora Sandes and the Serbian Army

Inspired by some of the Serbian soldiers whom she met, it was suggested to her by them that she was wasted as a nurse and that she should enlist as a soldier and during the course of 1915 she attempted to get to the front line and eventually joined the ambulance of the Second Serbian Regiment at Babuna Pass. Following a Serbian retreat through Albania as a result of an Austrian offensive, all the other ambulance staff either fled or were killed and, as Flora could no longer make herself useful as a nurse, she was enrolled as a private in the Serbian army and before long proved herself effective, being promoted to corporal.

Inspired by some of the Serbian soldiers whom she met, it was suggested to her by them that she was wasted as a nurse and that she should enlist as a soldier and during the course of 1915 she attempted to get to the front line and eventually joined the ambulance of the Second Serbian Regiment at Babuna Pass. Following a Serbian retreat through Albania as a result of an Austrian offensive, all the other ambulance staff either fled or were killed and, as Flora could no longer make herself useful as a nurse, she was enrolled as a private in the Serbian army and before long proved herself effective, being promoted to corporal.

The Decoration of Flora Sandes for her Bravery

In 1916, Flora was seriously wounded by a grenade during a Serbian attack after displaying considerable bravery for which she was rewarded with the Order of the Karadorde’s Star, which was the highest decoration of the Serbian military, and was promoted to the rank of sergeant major, receiving a number of medals. As Flora was unable to fight, she wrote her autobiography on her experiences and helped raise funds for the Serbian Army as well as running a hospital for injured Serbian soldiers, and after the war, a law was passed in Serbia making Flora Sandes the first female commissioned officer in the army.

In 1916, Flora was seriously wounded by a grenade during a Serbian attack after displaying considerable bravery for which she was rewarded with the Order of the Karadorde’s Star, which was the highest decoration of the Serbian military, and was promoted to the rank of sergeant major, receiving a number of medals. As Flora was unable to fight, she wrote her autobiography on her experiences and helped raise funds for the Serbian Army as well as running a hospital for injured Serbian soldiers, and after the war, a law was passed in Serbia making Flora Sandes the first female commissioned officer in the army.

Flora Sandes after World War I

After the war, Flora married a Russian émigré from the Revolution of 1917 and the couple lived in France for a time before returning to Serbia, which was now part of the new country of Yugoslavia, although after the death of her husband in 1941, Flora returned to live in Britain, where she died in 1956. Flora Sandes is unique in the sense that she remains the only British woman to officially serve as a soldier during the First World War, breaking all the rules and protocols of the time regarding the role of women in society and in conflict and successfully challenging the British government, which did not want her to serve.

After the war, Flora married a Russian émigré from the Revolution of 1917 and the couple lived in France for a time before returning to Serbia, which was now part of the new country of Yugoslavia, although after the death of her husband in 1941, Flora returned to live in Britain, where she died in 1956. Flora Sandes is unique in the sense that she remains the only British woman to officially serve as a soldier during the First World War, breaking all the rules and protocols of the time regarding the role of women in society and in conflict and successfully challenging the British government, which did not want her to serve.

Mr Goodall, Head of History

Harold Gillies:

Harold Gillies:

A local Revolutionary

The Early life of Gillies

- Harold Delf Gillies was born on the 17th of June 1882, in Dunedin - a city on the southeastern coast of New Zealand’s Southern Island.

- The son of a parliamentary member, Gillies’ early life was marked by privilege and curiosity - having attended the Wanganui Collegiate school in his Secondary School years, in which he competed in cricket, golf and rowing, before eventually commencing his medical studies at Caius College, Cambridge.

- Upon graduating, he soon completed clinical training at St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London under Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) Surgeon Milsom Rees - eventually receiving his medical degree and becoming a practising physician.

The Emergence of a Problem

- Upon the outbreak of the Great War in July 1914, Gillies was still serving under Rees, until he began volunteering with and serving in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC) in 1915. Eventually, he was stationed in France as a Surgeon General: the highest rank that could be bestowed upon a Regimental Medical Officer.

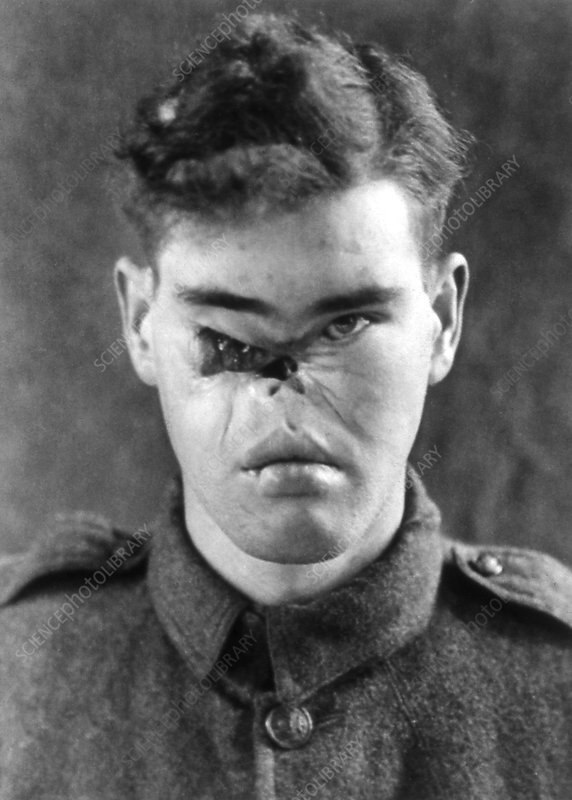

It was during his time in France that Gillies was introduced to the ever-increasing severity of facial wounds sustained by those fighting in the War: an increase indubitably a result of the emergence of new forms of weaponry.

It was during his time in France that Gillies was introduced to the ever-increasing severity of facial wounds sustained by those fighting in the War: an increase indubitably a result of the emergence of new forms of weaponry.- Prior to the First World War, most injuries sustained in battle were caused by those of firearms or blades - often posing little harm to many soldiers, who were simply content with being lucky enough to escape alive.

- Yet, with the Great War, followed the introduction of extensive, lethal weaponry: Heavy Artillery and Munitions, Machine Guns and the onset of Poison Gases (Notably Chlorine, which was first employed by the Germans at the Second battle of Ypres in April 1915) inflicted facial injuries to an unfathomable scale.

- Shells stuffed with shrapnel were arguably the most significant cause of traumatic injury - piercing through the flesh of a cheek with ease.

- These injuries were also exacerbated due to the lack of early treatment: many of these wounds were impossible to treat on the front line, forcing many surgeons to haphazardly stitch wounds together that, once healed, would stretch and distort the face - rendering some men unable to eat or drink or with gaping facial holes.

The Queen’s Hospital

The Queen’s Hospital

- Gillies returned to England in 1916, and began to set up a ward for facial injuries in Cambridge. On the 1st of July 1916 - the first day of the notorious “Battle of the Somme” - Gillies realised that his Hospital was without both the beds and space needed to treat those wounded.

- As a result, Gillies persuaded his medical officials to establish a larger facility, with specialised surgeons and equipment, in order to make scientific advances and treat patients with facial scarring more effectively.

- His requests were met, and in 1917 “The Queen’s Hospital” was established as the world’s first ever hospital dedicated solely to the treatment of facial injuries in our local town of Sidcup, (then) Kent - which endeavoured to reconstruct the faces of wounded men in order to allow them to live as normal life as possible.

“Skin Grafting” and Surgical Marvel

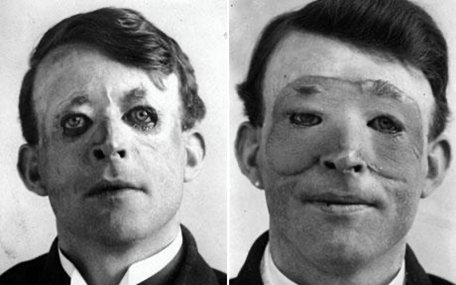

- Gillies realised that the best way to treat those with facial injury was to shift healthy tissues back to their natural positions. Then, any areas that were without tissue could be reconstructed using pieces of healthy skin from elsewhere on the body - a practice known as a ‘Skin Graft’.

-

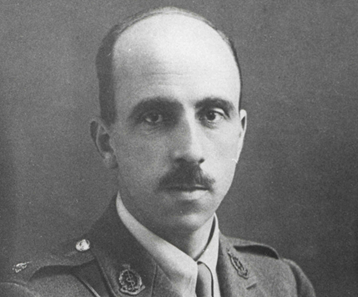

Usually, most skin grafts involve taking a flap of skin elsewhere (known as a “Pedicle”) and wrapping it around the wound without severing the flap’s connection to the body. This traditional technique was successfully performed in 1917 on Walter Yeo (right), a naval officer who had lost both eyelids in 1916 at the Battle of Jutland.

Usually, most skin grafts involve taking a flap of skin elsewhere (known as a “Pedicle”) and wrapping it around the wound without severing the flap’s connection to the body. This traditional technique was successfully performed in 1917 on Walter Yeo (right), a naval officer who had lost both eyelids in 1916 at the Battle of Jutland.

Achievements and Legacy

Dubbed the ‘Father of Plastic Surgery’ for his groundbreaking techniques, Gillies revolutionised the way in which plastic surgery was perceived and used for centuries to come - with many of the reconstructive techniques that he began to implement (such as his “Tubed Pedicle”) serving as the foundation for modern plastic surgery as we know it. His attempts at providing those gallant men who accrued life-altering injuries extended far beyond the surgical room, even introducing training schemes for his patients, so they could develop new skills, fit to combat the disadvantages they could face in the labour market. Additionally, Gillies’ endeavours conceived the concept of “Cosmetic Surgery”, with his admirable focus on restoring a “normal” appearance for veterans, allowing for freedom of choice regarding the features which they were to have transplanted. Yet, above all, Gillies’ commitment to the practice of plastic surgery serves as an ever pertinent reminder of the unwavering commitment of those who sat behind the front lines: whose efforts to improve the lives of those permanently afflicted by the First World War are not just mere pages in history, but a testament to the boundless capacity of a man to make a difference.

River Wattret, Year 12